N° 43 <br>Birthe Leemeijer / Lara Almarcegui

Please note: Flash 7 or higher is required to properly view this website.

Click here to download and install the latest version of Flash

N° 43 <br>Birthe Leemeijer / Lara Almarcegui

Please note: Flash 7 or higher is required to properly view this website.

Click here to download and install the latest version of Flash

30 January - 7 March 1999

A simple sign. This, she decided, was all that she would take to AVRO's Kunstblik (1998) - a television program by the presenter Angela Groothuizen and museum director Liesbeth Brandt Corstius, in which the audience is allowed to state its preference concerning works brought in by artists. An art program where one can sign up for a favorite painting or tempting piece of sculpture. And where a number of chosen individuals (who drew lots after having providing the right answer to a quiz question) are to consider themselves lucky to have just won a costly object. There stood artist Birthe Leemeijer (1972) with her sign amid the enticing canvases. Among the paintings and sculptures, she offered a fragile promise: on her sign, in Dutch, stood the phrase "I'll show you the most beautiful thing I know." To what place would she take you? What new thing would she show? And what would you yourself choose as the most beautiful thing you know?

Perhaps Leemeijer would lure us to the beach near Vrouwenpolder and invite us to take a seat on the enormous swingthat she placed there, in the surf, in 1996. Who knows, she may just get you to shear across the tops of the rugged waves and whip up high to see across the sea. Or (as with her contribution to the Rotterdamse Architectuur manifestatie) she might take you on a balloon ride to enjoy the passing land-scape from a great height. She may. Or may not. The winner to whom Leemeijer has redeemed her promise keeps the experience to himself. Nor does the artist say anything. Her work existed only for a short time; the special experience is shared only by two people.

Her work thereby seems to be linked with the 'new or social performance' with which a flock of young artists attempts to intensify personal contact with the audience. One such project was Dreamkeeper, where the Spanish artist Alicia Framis presented herself as a guardian of dreams who would be at one's side while one sleeps. Another was the exhibition held in Maastricht De koffer van de celibatair (The Celibate's Suitcase) (1995), by which Suchan Kinoshita invited visitors to sign up for a 24-hour trip with her.

For Leemeijer, however, the promise has already done its job even before it has been redeemed, even before the encounter with it takes place, even before she has shown the most beautiful thing she knows. Once the audience has produced its own mental picture of her promise - once the work has been completed, in other words, in the audience's imagination - then Leemeijer has succeeded in her objective. To arouse the imagination she needs no canvas, paint, marble or photographic paper - nor does she need the closed space of a museum or gallery. Reality itself serves as material for Leemeijer.

A single remark is sometimes enough. Just as, during the mid sixties, Stanley Brouwn asked passersby to show him the way by drawing this on paper for him (This Way Brouwn) and thus prompted them to imagine the streets used by them every day, Leemeijer asks one to picture the most beautiful thing one knows. And just as Brouwn and other artists of the sixties refused to acknowledge the dividing line between art and reality, Leemeijer asks for a consideration of experiences in reality. After all, the experience that a 'work of art' offers one can also be found in reality. The world, the landscape - these are the sources from which Leemeijer draws directly, without the intervention of paint on canvas or paper.

For the Prix de Rome of 1997, Leemeijer asked four residents of Hoorn to take her on a walk through the town. The descriptions of these routes were compiled by her into four brochures that can be obtained from the VVV (tourist board) in Hoorn. Unlike Brouwn's request for route indications from passersby, that of Leemeijer focuses not only on stimulating the imaginations of the four walkers. Leemeijer takes this further: with her walks she entices anyone and everyone to place themselves in someone else's shoes, and she attempts to provide an alternative to the city's existing approach to tourism by discovering other forms of beauty in the urban realm. Take the route, for instance, that has been mapped out by a blind person (indicated in the guidebook by the number of strokes with a stick and the ridges along the way). Experience the way in which the stench of a urinal can help in finding one's direction. Allow the meteorologist to show the way via the clouds. Or follow the route described by a paver of streets - looking down all the way. Leemeijer deals in experiences - those of others or her own. She gathers them, and then passes them on. Leemeijer merely creates the conditions for others to participate in these. In Uitzicht (View) (1997), she asked three pedestrians to select the bench with their favorite view. At set times Leemeijer could be found sitting on the benches, ready to talk with others about the view. During Rotterdam's architecture event AIR Zuidwaarts/ Southbound (1998), she was asked to inspire architects for urban development in the direction of 'de Hoeksche Waard'. Leemeijer conferred with them on descriptions made by inhabitants of this island; these had been written down during a balloon ride over the area. Whether or not the offered experience should be regarded as art - that makes no difference to Leemeijer. So long as the view provides insight into a new experience or a passing moment.

The Spanish artist Lara Almarcegui (1972) also searches for insights, sometimes in order to enrich the audience with an experience and sometimes to fathom the space that surrounds her. When Almarcegui was given a space at De Ateliers in 1996, she began to ask herself what it actually was: that big, white studio that she couldn't describe as being any more than 'big' and 'white', no matter how long she looked at it. A bare space, ready for use, void of character. And like an exhibition space, she realized, it was ready to swallow up and leave no trace of all the impressions, stories and events of previous users.

Almarcegui turned her back on the studio. She dedicated the first months of her stay at De Ateliers to exploring the other spaces in the building. Spaces that had no use, such as old rooms in the attic and in the damp basement. Spaces that had no users and were deprived of any potential use due to their nature, their situation or their advanced state of neglect. These Non Delimited Rooms, which proved to be the complete antithesis of the studios, were charted out by Almarcegui in a 'tourist guide' which is available to any visitor or newcomer to De Ateliers on entering the building. With the utmost precision she describesthe characteristics: the draught that brushes across one's hand, the odor in the basement, the sound of a low-flying aircraft or a rumbling pump. Affectionately she points out the imperfections (the walls warped by dampness, exposed constructions, a waterpipe that leads nowhere) and describes the 'curiosities'. As with the attic room: "A place speaking about memory, privacy and time. Here you will see a ceiling held by planks and that the solid walls of the big white corridors behind are made of wood, which swells up, goes down, gets old, dries up, erodes to sawdust. Here you count five different kinds of wood, revealing a humble construction, improvised, spontaneous and human. It smells of old wood, dusty. One expects to come across a mouse at any moment. That De Ateliers could have such a familiar space, changes all ideas one could have had about the building." Almarcegui seems to be constantly in search of the opposite, the negative, the reversal of things. She seeks, in contrast to static studios, the spaces imbued with history and decay. Rather than making the usual cursory reference to the facade in her 'tourist guide', she works her way to the inside. And on being invited to take part in an exhibition held in a market building that was scheduled for demolition (Mercado de Gros, San Sebastiàn, 1995), she went to the effort of restoring the outside of the building up to the day of its destruction.

For hours, days, months, Almarcegui perseveres in exploring a place. She is well aware that the time and energy that she puts into this are often not in proportion to the result achieved; but that humble, almost servile attitude with respect to a place is, for her, the only method for penetrating a space. Once, on a vacant lot in Amsterdam, she dug a deep hole that was to expose the mysteriousness of the ground. And for a day, she went about touching the walls of an exhibition space - like a lover caressing the skin of her beloved with her fingertips, getting to know its every irregularity. For Bureau Amsterdam, Almarcegui has produced a guide to the wastelands of Amsterdam: to vacant lots and polluted sites, to speculative properties or desolate industrial areas. Her Wastelands Map Amsterdam brings to mind the wastelands that land artist Robert Smithson began to visit regularly in 1966 - of the abandoned coal mines and industrial areas that he photographed and filmed, and which he presented in his Sites/ Nonsites as antitheses to the artificial exhibition space.

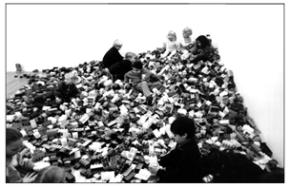

On the trial map that Almarcegui produced for Wasteland, the vacant lots are clearly indicated and historical monuments are rubbed out. The map gives no consideration to the buildings that guard the past. Her tourist guide focuses on the vague areas that have lost all function, on the building sites that hover between past and future, and on the empty spots that have yet to be filled in. Whereas Almarcegui merely invites one, at Bureau Amsterdam, to pick up her map and then quickly proceed into the city, Leemeijer has filled its space in order to allow the city to come inside. She has filled the space with twenty-thousand blocks: with toy blocks spray-painted in countless colors, with toddler-sized plastic bricks. Children from the younger classes of a few Amsterdam elementary schools have been invited to come and build. To make shelters to suit one's needs and one's state of mind: places for hiding, little corners for seclusion, open spaces for playing or - if happens to end up that way - perhaps a cheerful, multicolored artwork.

Anne van Driel

Translated by Beth O'Brien